Women in blue saris playing cards, B Prabha

Women in blue saris playing cards, B Prabha

George Keyt‘s cubist work, Woman in a Blue Sari, mid 1940s

George Keyt‘s cubist work, Woman in a Blue Sari, mid 1940s

Women in blue saris playing cards, B Prabha

Women in blue saris playing cards, B Prabha

George Keyt‘s cubist work, Woman in a Blue Sari, mid 1940s

George Keyt‘s cubist work, Woman in a Blue Sari, mid 1940s

First up, Jayalalitha looking quite magnificent as Cleopatra [X]

First up, Jayalalitha looking quite magnificent as Cleopatra [X]

Not as magnificent but Ranveer Singh nicely fills out Arjun Saluja’s designs in a photofeature for Platoform Magazine.

A look at how past fashions influence modern fashions:

Detail from Warren Hastings with his wife and Indian maid, painted sometime between 1784-87.

Detail from Warren Hastings with his wife and Indian maid, painted sometime between 1784-87.

Floor length “anarkalis” (no doubt known by a different name) can be spotted in 18th century/19th century paintings. The girl here is obviously dressed in her best, teaming it with a gold edged dupatta, jewellery and red and gold jootis. This was probably teamed with tight trousers underneath, they can sometimes be seen when the tunic is translucent. This is quite similar to styles today, including the long net/chiffon sleeves that are seen today.

I was at a store recently and the man there informed me that the anarkali trend is about 7 years old and still popular. A few recent examples – [X] [X]

A floor length variant was worn by men too, as in another painting by Zoffany.

There are a number of 19th century versions of the “sari” which are more like the half-sari or the ghaghra-choli. More than a few modern interpretations of the sari, including the lehenga sari, rely on variations of this kind of attire. Some do away with the pleats, some retain them.

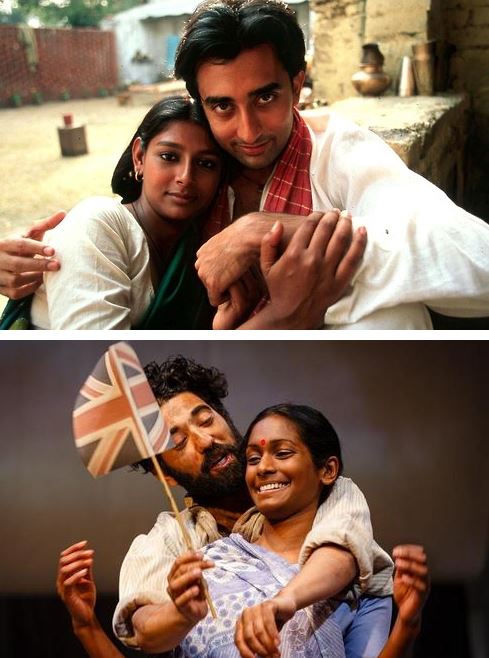

Ayahs on film: Nandita Das in Earth.

Ayahs on film: Nandita Das in Earth.

Ayahs on Stage: Anneika Rose in The Empress.

By the 1930s the image of a cherished ayah had been enshrined in the nostalgia of the Raj that had been generated at the close of the nineteenth century. As that image took on a life of its own, individual recollections of British colonials were compressed and compelled into the one abiding memory, as Margaret MacMillan put it, of “a much loved ayah, usually a small, plump woman with gleaming, oiled hair, dressed in a white sari, who had sung to them, comforted them, and told them wonderful Indian stories”. Responding to the West: Essays on Colonial Domination and Asian Agency, edited by Hans Hägerdal.

In addition to the ubiquitous ayah, cooks, gardeners, syces, and many other Indian domestics in colonial households influenced the daily lives of young residents. The results were predictable: British children grew emotionally attached to their ayahs and other Indian attendants, and they frequently acquired more familiarity with and fondness for the language and culture of these people than they did for the European heritage of their parents* The Magic Mountains: Hill Stations and the British Raj, Dane Keith Kennedy.

The British in India, from the very beginning, were expected to maintain an establishment with a good number of staff. There are several accounts of the expenses incurred by domestic staff as early as in the late 18th century. In letters home the problems and the conveniences of maintaining an establishment are detailed. Of all the employees a British household had, the ayah was the most cherished (though there are negative accounts too, particularly in the initial years of the British in India). Functioning as domestic help but largely associated with being an Indian nanny, they appear in paintings and pictures on the 19th and early 20th century (the earliest probably being Joshua Reynolds portrait). Partly this was to document – and perhaps boast – of their lives in India. Partly this was because social intercourse with Indians for the British was often restricted to their domestic staff, few Indian middle class families permitted the inevitable interaction in the public sphere to spill over into the private.

There are numerous photographs of ayahs, often seen with their wards and sometimes as part of a family picture. Almost always they appear in white saris with coloured borders, teamed with a printed or plain blouse. Ayahs were amongst the first Indian women to travel abroad on work, often finding themselves in a precarious position. By the 1950s, the saris are depicted a lot brighter as in this oil painting in London.

[X]

*For precisely this reason, many British children were sent back home to boarding schools at an early age.

Note: Maids, attendants and the like also occur in Indian miniature paintings and in ancient Indian art, often as intimates, in for e.g. a woman at her toilette, delivering love messages etc. I won’t be covering that at the moment.

Portraits of ayahs. Some initial works show ghaghra cholis and coloured saris while later works often show women in white saris.

Portraits of ayahs. Some initial works show ghaghra cholis and coloured saris while later works often show women in white saris.

Sources (incomplete): [X] [X] [X]

A number of fashion blogs feature couture, pretty stuff, beautiful fabrics, embellishments, trends and women admired for their beauty. Which is fine for the most part, it is what elevates clothing above the mundane. Once in awhile though it is more interesting to look at everyday, hard working clothes. The way they speak to us about the dignity of the women who wear them, the feminine embellishments incorporated in it and the beauty of worn and sparse clothing.

Today’s post is on the Ayah. A term prevalent during the Raj that is no longer used but once a catch-all term for the domestic help ubiquitous in Indian households, especially with regard to the care of children. I myself had an ayah as a child. She was a Burmese Indian who had been expelled in 1962 and quite old when she began working for my parents. I still remember her sweetness and warmth, the comforting smell of her much worn sari. These posts are dedicated to her.

Angelo da Fonseca, who was known for his Indianised Christian themed art.

The two paintings, dated 1967 and 1959, represent the two most common dress forms worn in India, the sari and the three piece that includes a dupatta and kurta teamed with a salwar/chudidar.

Source: X

The Reis Magos Fort in Goa has an exhibition of Mario Miranda’s 1951 illustrated diary. It is an amusing and interesting look at Goan society (largely the Catholic part of it) circa 1951. I loved the captions and little quirky insert panels as in the one featuring a village woman with a pot on her head. A lot of late 40s/early 50s fashion. Often influenced by Portugal (in one Mario records the clothes ordered from Portugal) and closer home, the then Bombay.

In the illustrations Kashi is definitely the loveliest of the women featured. That kind of top as well as Goan fashions is featured in many movies set in Bombay and Goa (e.g. the 1952 Jaal, the 1973 Bobby), albeit in it’s Bollywoodised version.

In the illustrations Kashi is definitely the loveliest of the women featured. That kind of top as well as Goan fashions is featured in many movies set in Bombay and Goa (e.g. the 1952 Jaal, the 1973 Bobby), albeit in it’s Bollywoodised version.

My grandparents came from the villages around Kumbakonam but lived most of their adult lives in Maharashtra and Bihar. My great grandparents had a house in Tiruvidaimarudur, they moved here in the 1950s from Mumbai. Given their long lives, we visited them a few times as children. I went back for a brief visit after many many years. It refreshed my memory and I added new ones and came away with my heart and mind full of the images of Kumbakonam, despite a later visit to Goa.

A few pics of the girls and women in and around Kumbakonam. 1: A fresco at the Darasuram temple, this temple was astonishingly beautiful and I was a little surprised to find that a number of frescoes feature larger women; 2: Also at the Darasuram temple, a dressed idol of Vishnu Durgai: 3 & 4: A handloom nine yard sari and mill made polyester six yard sari on older and younger members of my family 5 & 6: Aruljyoti in the morning on her way to work 7: A man’s shirt worn over a sari on Andhra immigrants. Commonly worn by women who work in the fields or do manual labour in the state as far as I can see 8 & 9: Salwar kurtas on girls at the river – this has replaced the pavadai and the half saree for young unmarried women in all but the more conservative families. The convenience of hooking safety pins to a chain/beads remains:) 10& 11: Tinsel and Sequins are the new black of India, it is fairly common in rural Tamil Nadu on young girls as well as older women 12: This pushy young girl got about 20 pictures taken of herself with a friend. Her puff sleeves rival Anne Shirley’s.

Shabana Azmi’s cotton saris in Swami (1977) [X] set in rural Bengal. There is a long history of cotton clothing from Bengal and the woven cloth has distinctive patterns so that even most urban users can recognise a Bengal sari. Actual cotton production in Bengal appears to date from the 1780s, perhaps as Bengal cotton began to be exported to England. More Shabana here [X] [X]