I had a bit of a meandering look at the history of hairstyles in India on tumblr and as always this post collates it on wordpress.

curnakuntala (Sanskrit): locks or ringlets hair style.

alaka-avali (Sanskrit): hair arrangement in spiral locks

dhammilla (Sanskrit): hair bun

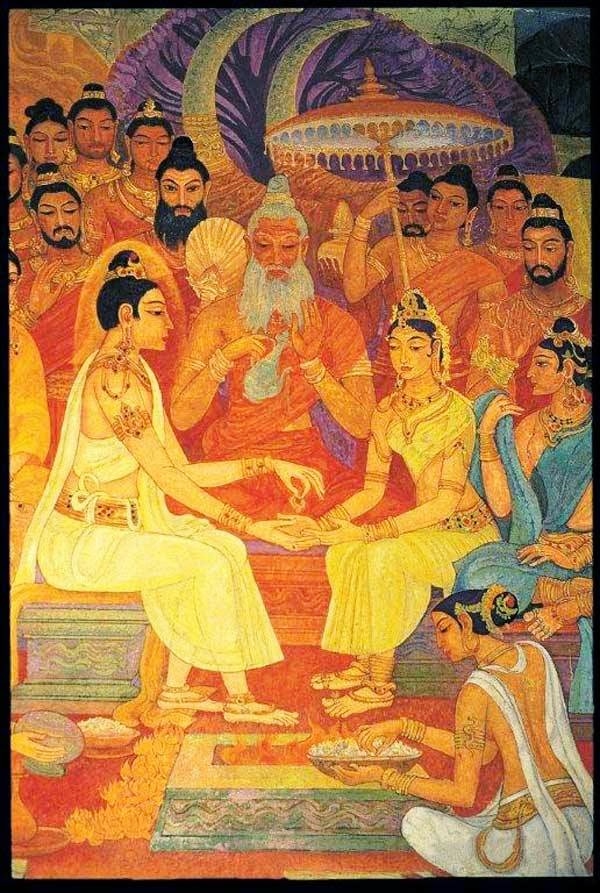

You could blame the Greeks but for a period of time everyone in the subcontinent was seemingly mad for curls. And ringlets and waves and completely improbable spherical somethings (though the last was probably confined to sculpture). The beginnings seem to be in Gandharan art and representations of the Buddha but curls and elaborate coiffures appear in sculpture, literature and art for at least a few centuries later in different parts of the sub continent. The Gupta Age is probably the most classical style (see also X), the curls gradually disappearing from Indian art over later centuries.

Apart from the curls, the elaborate hair bun (I think the dhammiila is similar to the modern day khopa) was all the go. To this you could – if you wished – pin dupattas, flowers or jewels to give a style that recurs throughout Ancient Indian art.

In the pics: 1- Head of Parvati from Ahichhatra, U.P. 5th century, 2 – detail from 12th century sandstone from Madhya Pradesh, 3 – Ajanta fresco.

O your hair, he said,

It is like rainclouds

moving between branches of lightning.

It parts five ways

between gold ornaments

braided with a length of flowers

and the fragrant screwpine. From the Kalithokai, translated by AK Ramanujam.

I have probably seen this photograph all over the internet but it also probably best fits the poem (bar the screwpine).

The five different hair styles usually mentioned in Sanskrit and Tamil texts include hair in a knot, hair gathered in a bun, hair curled, hair parted and hair plaited. The last, the veni, as everyone is aware has a long history and is often embellished with flowers and jewels.

The beauty and eroticism of wet hair – loose, yet to be braided, perhaps perfumed a little after a bath – recurs throughout Indian art and literature. Almost always the setting is outdoors, whether natural or landscaped.

Sanskrit literature is much given to conceits – with wet hair it plays on the beauty of water drops wrung from hair. Women drying their hair after their bath are usually depicted with a hamsa – the bird mistakes the water drops for pearls. Not entirely clear but depicted in the 8th-11th century sculpture from Morena, UP in pic 1 and here.

Wet hair and beauty rituals of the bath are also seen in a number of miniature paintings like in pic 2 (18th century, Bikaner or Deccan).

Then again in colonial paintings as in pic 3 (Bengali woman wringing out her hair after bathing).

The early 20th century boasts a number of paintings titled After the Bath. One amongst several similarly titled works of Hemen Mazumdar (pic 4).

Pic 5: Contemporary photograph via Getty Images.

the sight of me combing my long hair

brings you back to your country

where you tell me

girls sit in the open air

combing each other’s hair. Poem for an Indian Scholar, Crazy Melon and Chinese Apple, The Poems of Frances Chung.

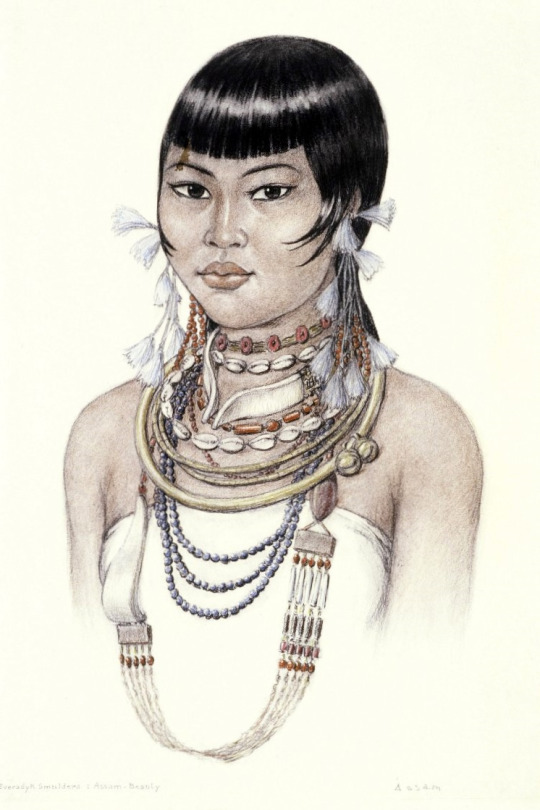

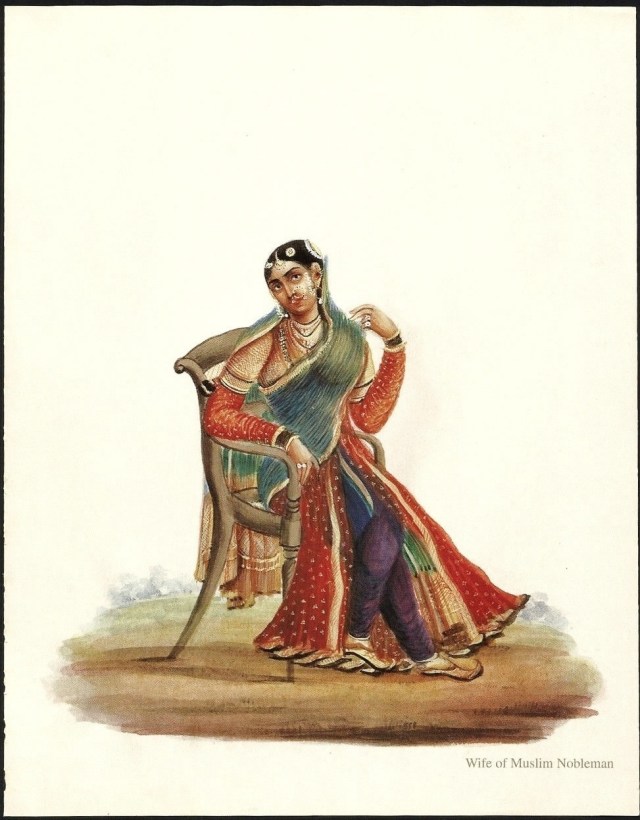

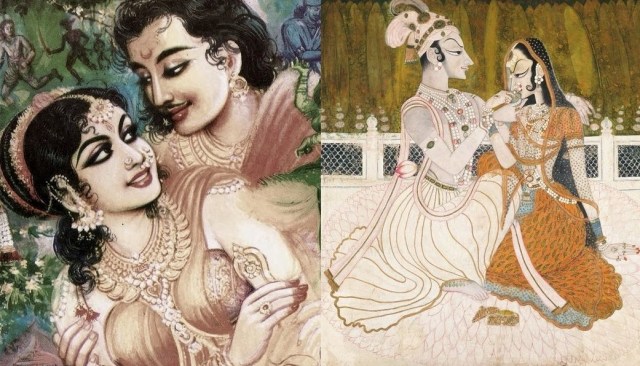

Perhaps it is the nature of miniature painting but for most of the 16th-19th century hairstyles are flat and either depicted loose or plaited (also in company paintings/Kalighat paintings.). As always with Indian hair jewels and flowers are present minimally or in abundance. In miniature paintings additionally hair is often partially covered with an odhni.

The second painting depicts a nayika whose lover/husband is devoted to her (swadhinabhartruka). Often paintings depict these nayikas having their foot decorated or having their hair dressed. This can also be seen in sculpture (e.g. Shringhar, Kushan period) but in miniature paintings the nayika and her lover are usually Radha and Krishna.

Pic 1 (Hyderabad, 1840). Pic 2: Kangra, 18th century.

simanta (sanskrit): sima + anta – boundary line/hair parting.

The hair parting itself may be a decorative aspect of the Indian hairstyle. Additionally flowers or jewellery can be arranged along the parting (e.g. mang tikka as in pic 3 where a pendant is added and also substitutes for the bindi). Apart from the decorative aspect, there are ritual aspects to the hair parting. E.g. the sindoor as a mark of marriage (on Konkona) in some parts of India or the simantonnayana (arranging the parting of the hair) ceremony. See also X.

In the pics: Sulochana, Konkona Sen Sharma, Sitara Devi.

Their hair shimmered with an intense shine

and gave off a beautiful scent. Virsinghdev Charit, Keshavdas.The hero was handsome

with oiled, curly hair, on which

fragrant pastes and perfumes

had been rubbed. The Handsome Hero, Kurinjipattu

You didn’t step out without a slather of hair oil, preferably scented, up until the middle of the 20th century in India. Advertisements of the 40s and 50s promised black, glossy and groomed hair, many products were also strongly scented. Sometimes they made use of new ingredients like the glycerine of pic 3, sometimes they played on Indian tradition.

Pic 2 is for Himani.

A look at hairstyles in a brief window of time: 1930s-1960s.

A look at hairstyles in a brief window of time: 1930s-1960s.

1930s: MS Subbulakshmi’s naturally wavy hair, a bit of finger wave for Miss Gohar.

1940s: The double choti on Baby Sulochana, perhaps a bit of a perm/roll for Brijmala.

1950s: Plaits and ribbons for Vyjayanthimala, a bit of wave and hairband for Roopmala.

1960s: Asha Parekh in a bun encircled with flowers, Unknown lady in a piled high hairdo.

And even now, instead of working, I visualise her, a pale silhouette in a sari of blue silk, all interwoven with gold thread. And her hair! The Persians were right, in their poetry, to compare women’s hair to snakes. What will happen? I do not know. Maitreyi, Mircea Eliade.

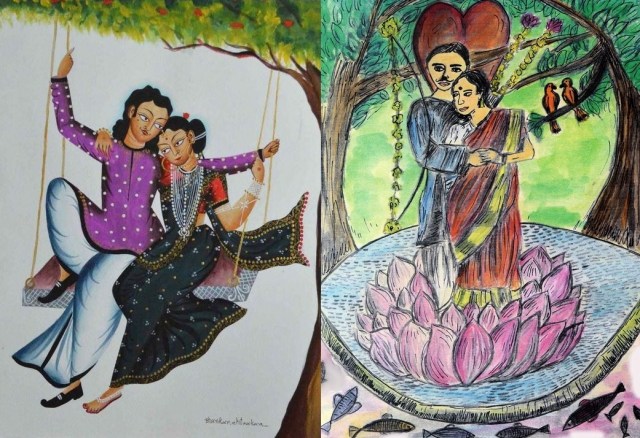

Though there is many an Indian song dedicated to it, in my view the beauty of unbound tresses is most seen in Bengal (normally seen on younger women, older women tend to tie the hair in a bun or plait). Not the heavily styled and waved kind, just the natural fall and flow of tresses. Usually it is worn unadorned but Mrinalini and Lotika, the daughters of Manmohan Ghose, have styled it with ribbons as was common in the late 19th/early 20th century. This is probably late 1910s or early 1920s.

Pic Source. See also X, X, X.

Some forms of hair decoration (e..g the gajra) predominate in India. Like leaves are sometimes worn as a hair ornament in tribal communities in India (X, X). Flowers with elongated petals that resemble leaves are also worn. The arrangement of flowers of this sort, e.g. palash which is worn in the hair or lotus as in this painting is similar to the sun ray like hair ornaments often seen in vintage photos.

Some forms of hair decoration (e..g the gajra) predominate in India. Like leaves are sometimes worn as a hair ornament in tribal communities in India (X, X). Flowers with elongated petals that resemble leaves are also worn. The arrangement of flowers of this sort, e.g. palash which is worn in the hair or lotus as in this painting is similar to the sun ray like hair ornaments often seen in vintage photos.

The painting: Charm of the East, AR Chughtai.

For previous posts on hair styles and decoration, see:

The 70s updos; In the 60s; The 60s bun; 1950s Ribbons; The evolution of ribbons; The 1950s hair style guide; The Jabakusum ad; The gajra post; Flowers in the hair; The plait; Nair hairstyles; Medieval Karnataka.

Yashodhara and Rahul meet the Buddha

Yashodhara and Rahul meet the Buddha