The bindi/pottu/sindoor/tikli – whatever name it be known by – is probably the most emblematic of Indian elements of attire and also has a long history. It is symbolic (as a signifier of marital status or of caste), part of the daily ritual as well as decorative. While several terms exist, I will use the term bindi in this post.

The bindi as a symbol of marital status in women (Kumkum/Sindoor) is familiar to most Indians. This can vary from region to region and does not always involve the hair parting, but in almost all parts of the country it is a part of Hindu marriage, festive and temple rituals. Its origin is obscure but it possibly was a blood mark of sorts to mark the bride’s entry into a new family, this later being replaced by kumkuma which was a mix of turmeric and slaked lime. Not as commonly worn as a few decades back it remains a part of rituals and is often applied in conjunction with decorative bindis.

The bindi as a symbol of marital status in women (Kumkum/Sindoor) is familiar to most Indians. This can vary from region to region and does not always involve the hair parting, but in almost all parts of the country it is a part of Hindu marriage, festive and temple rituals. Its origin is obscure but it possibly was a blood mark of sorts to mark the bride’s entry into a new family, this later being replaced by kumkuma which was a mix of turmeric and slaked lime. Not as commonly worn as a few decades back it remains a part of rituals and is often applied in conjunction with decorative bindis.

Her friends apply coolants: fresh lotus leaves, bracelets of lotus fiber, sandal wood paste; they fan her with palm leaves. [X]

Decorative designs for the face and body are found in plenty in Sanskrit texts, some seem to have been very elaborate given they start at the breasts and literally bloom on the face. The practice was more common in spring and summer and the ingredients used were cooling in nature, with the coming of winter the paste was minimally applied, if at all. Designs were usually made from a paste of sandalwood, musk and/or saffron and were commonly known as पत्रावली/patravali (a garland of leaves/foliage).

Sandal paste patterns in conjunction with kumkuma and ash were also indicative of castes and sects, the latter persists now and then among men. For women the practice of using sandal paste on the forehead is now reduced to a spot or dash often worn with a bindi or as bridal decoration.

While sandal paste is used to make designs and applied as lines/a band, turmeric was used on the forehead as a band. Like sandal it has decorative and cultural aspects and is used for skin care.

Pic 1: Veena in Samrat Ashok (1946), Pic 2: Portrait of a Lady, 18th cent., Pic 3: Untitled B.Prabha (1960).

A spot of chalk and another of vermilion shone upon her forehead, like the sun and moon risen at once over a lotus leaf. On Radha as a bride, Harkh’nath.

The designs referred to earlier persist in some ways, e.g. bridal designs for the forehead are seen in several parts of India and especially in Bengal where sandal paste is often applied to make the design. The photograph here is of a Gujarati bride (an Asha Parekh role?!), I think perhaps in the 60s-70s. Another Gujarati bride here.

Must be the purist in me but I can’t get on the sticker train for this:)

Decorative facial designs by way of tattoos or black dots is common in rural and tribal India. The application of three dots on the chin is one of the more common rural designs and expectedly often made a screen appearance.

In the pics: Sreela Majumdar in Mandi (via dhrupad), Vyjayanthimala in Ganga-Jamuna and Nargis in Mother India.

Specific designs are often seen in medieval and later Indian paintings. An e.g. is the straight line on the forehead seen on Deccan women as in this MV Dhurandhar illustration. Another example is the chandra-bindu or the moon bindi. Which is also a Sanskrit character. In bindi form the dot may be placed within the half circle or outside it. Though worn elsewhere in Western India, it is characteristic of Maharashtra (pic 1) and can be combined with further lines and dots. A mang tika (forehead pendant) can also function as a similar kind of bindi like in pic 4.

While all kinds of bindis from the sindoor to a round dot to lines to designs are seen in 20th century India, some types seem to dominate in the popular images (read cinema) in certain decades. The 1940s and 1950s stills often have a lot of different designs, sometimes these appear to suggest a particular aesthetic in historical or mythological films but they also appear in more modern looking publicity shots. The designs can be quite varied and complex though the flower bindi (pic 4) with its Bengal hints (red core with white dots) pops up quite often on 1950s actresses.

Pic 1: Nalini Jaywant, Pic 2: Sushila Rani, Pic 3: Shakila (courtesy photodivision) and Pic 4: Madhubala

The 1930s/1940s urban woman look required a very basic and small bindi . Where it is positioned on the forehead depends on the wearer. Shaping the eyebrows also seems to have been a thing in the 1930s and 1940s.

In the pics: Amrita Sher-Gil, Gayatri Devi, Devika Rani, Shanta Hublikar, Leela Chitnis, Miss Gohar.

These were also decades that did not require a sari to be worn with a bindi as in these pics (pic 1: Hansa Wadkar, pic 2: Neena).

The “tilaka” or the elongated forehead mark takes many forms, some of which have a religious function. It can also be present as an ornament (माँग टीका). It has a decorative aspect and can be drawn on as required by the wearer. While quite commonly seen in South India on young women, it is also prevalent in other parts of the country. Quite often seen in the 1950s and 1960s when it was worn by young women- you can see a few examples in today’s post.

Last pic courtesy photodivision.

By the 1970s and 1980s the simple round bindi was around, it could be applied as a powder or liquid but the presence of Shringar kumkum as well as the initial simple felt bindis meant that the latter were preferred. By the 1990s of course the felt decorative bindi we are familiar with had appeared.

In the pics: Rekha, Aruna Mucherla, Swaroop Sampat (still the Shringar kumkum girl).

And between the lac bindis of the early 20th century and the felt bindis of today there was the plastic stick-on bindi. Made of a stiff but pliable plastic, it had a bright and smooth surface and came in more than a few colours. It’s not hard to spot in photographs of the 60s and 70s but never replaced powder and liquid bindis like its felt counterpart.

Finally he appears with white fragrant paste on his body, a bright crest jewel, white silk garment with a yellow border of swans, tilaka mark on his forehead and ornaments round his hair, neck and arms. [X]

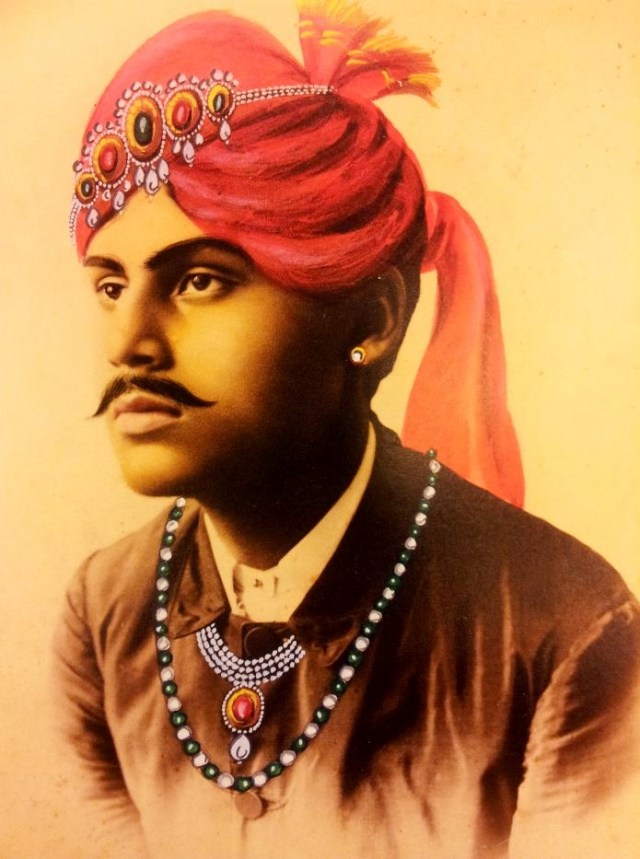

Various forms of the bindi, largely the round dot and tilaka, were also used by men. A band of sandal or turmeric across the forehead was also be worn by men. Often these serve as caste marks and include a mixture of lines, dots and tilaka. Usually drawn with sandal, ash or kumkuma they are more common in the Southern and Western parts of India. They also serve a decorative purpose, especially for a bridegroom.

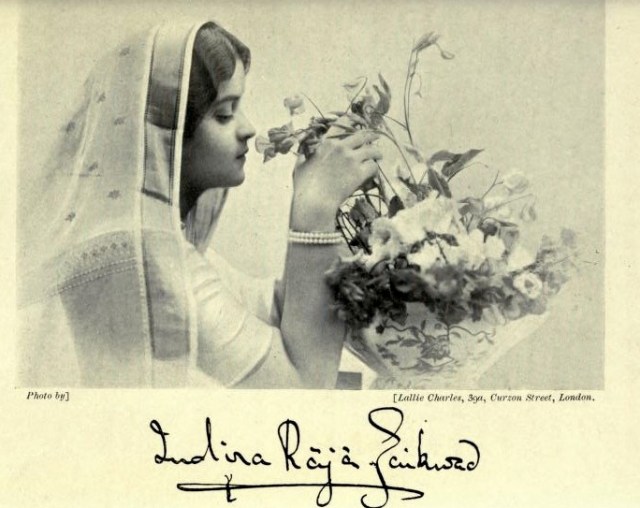

In the pics: Gandhara head (photograph mine), Krishna, Maratha chief, 1860, Maratha prince, late 19th century, Madhava Rao and Sir Pannalal Mehta painted by Raja Ravi Varma, Maharaja Sayaji Rao in 1902, Mysore raja in 1906, M.K. Thyagaraja Bhagavathar, bridegroom.

PostScript: Facial decorations are of course known all over the world, especially in tribal societies. Decorations similar to the bindi in more urban cultures occur in Mycenaean Greece and Tang Dynasty China (and can also be seen in Korean wedding rituals today). The Tang Dynasty in particular had many kinds of designs and a number of colors were used, though red predominated. As well as a story re its origin, the falling of petals on a princess’ forehead. Nevertheless the persistent and diverse uses of the bindi for ritual and decoration appears to be peculiar to India.

Mycenaean sculpture here. Recreation of Helen of Troy here. Tang dynasty lady here. Tang Dynasty recreation source here.

October is Marigold

October is Marigold

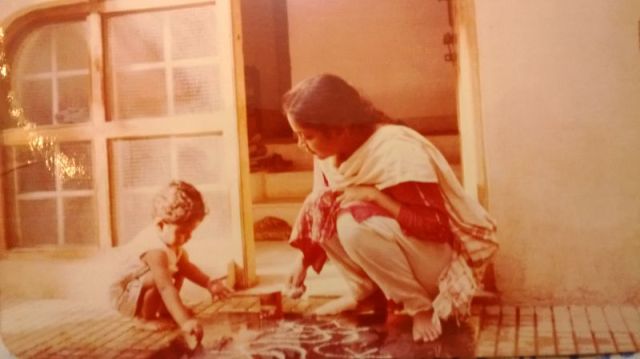

Making an Alpana, Santiniketan, 1954

Making an Alpana, Santiniketan, 1954

Maharaja Pratap Singh, Jammu and Kashmir,

Maharaja Pratap Singh, Jammu and Kashmir,